To be twenty-something is to be an active dreamer. You think about bigger picture stuff (world politics, the state of the economy, the state of technology, the state of art and commerce, fame, fortune and all the organic bits in between) and try to figure out how you, the twenty-something, fit into this big, broad game of life. Some twenty-somethings are mover and shakers that seem to have already conquered the world, while others try on different personas and job opportunities like trendy outfits.

When I was twenty something, I was in the midst of trying on lots of different personas. I was a writer, a journalist, a comedian and a bartender living in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I bartended at a tiny music club while struggling to figure out what to do with my life.

This was about when I first met Tony Maws. He was a sous chef at a fine dining restaurant and one of my late night regulars. He’d roll in at 1:30 in the morning with a bunch of rowdy kitchen guys and mouthy servers. They’d shout a flurry of desperate orders at me in hopes of beating the ticking clock of last call. Tony, with his long curly hair hidden behind a sweat-soaked bandanna, would shoot me an impish smile that could cut daggers through the dark and boisterous crowd of last-call ordering and put his request for a shot and a beer at the top of my priority list every time. After many visits to my bar (which always included a funny dance of gratuitous over-tipping and generous over-pouring), Tony and I became friends.

The thing about Tony that impressed me most was that despite all the whining and complaining of most of our twenty-something friends around us, he always knew exactly what it was he wanted to do. He’d tell me how he’d finish out “doing his time” cooking at the Blue Room in Cambridge, then work on the West coast, maybe spend some time in a kitchen in France and then, by the age of 30, he’d own and run his own restaurant. I remember the stunned feeling I had, that morning we shared a muffin and coffee at a local bakery, when he told me his plans for the future. His determination and drive made my head spin and made me wonder if maybe I should start thinking more about the direction of my life and less about “finding myself”.

Time passed and I started whittling down the many things I wanted to do and started focusing on one option: writing. In that time, Tony left town moved to Santa Fe and worked for Mark Miller at his highly celebrated Coyote Café in Santa Fe. Later, I heard through the restaurant grapevine that Tony went to France to work for Bernard Constantin at La Rivore in Lyon. I moved to Los Angeles to go to film school. Then, in 2002, I spotted Tony’s face on the cover of Food & Wine. I was happy to read that Tony had done just as he said he would. He was the chef owner of his own restaurant.

Craigie Street Bistrot

Living on the west coast as a film school student presented plenty of worthy distractions and even more financial obstacles to keep me from flying back east to try out the new restaurant of my long-ago friend. But then, after years of frustration over dead-end Hollywood jobs, I decided to move back home to Massachusetts for the summer to make some fast money bartending and waitressing at a busy sea-side restaurant and decide, once and for all, if I should give up on my dreams of being a screenwriter.

Strangely enough, one of the first things I did when I got back East was try to make a reservation at Craigie Street Bistrot. I was pleasantly disappointed when I heard a voice mail explain that the restaurant would be closed for the first few weeks of summer for “a well deserved vacation.” I smiled to myself as I hung up the phone. Without tasting a morsel of food or seeing his dining room, I already knew Tony’s restaurant would be unlike any other I had ever visited.

Booking a reservation

My east coast summer experiment offered many unexpected insights. I had changed. I didn’t fit into my small town. I thrived on the diversity of the city of Los Angeles. Most importantly, I realized that writing was in my blood—there was no avoiding it. So after a long and difficult summer in Newburyport Massachusetts, I was ready to move back to LA—for good. Just before packing my car up for the long ride west, I booked an early reservation at Tony’s restaurant for my sister and I.

Just blocks from Harvard University’s campus, Craigie Street Bistrot is a tiny place that requires patience in finding. Located on a side street in the basement of an unassuming brick building, the dining room of Craigie Street Bistrot is smaller than many of its well-heeled customers’ living rooms.

Chef Tony creates his menus daily, based on what is available from local purveyors and farmers. This is no little feat, considering the fickle New England weather and harsh winters Massachusetts suffers. Regardless of the season’s bounty or limited availability of anything beyond tubers and squash, Tony never fails to find inspiration for his ever-changing daily menu. Even when snowstorms strike and crops fail, his market fresh dishes are so delicious and thoughtful, diners often forget they’re in a small (albeit homey) and nearly windowless basement dining room.

His dishes engage the eater to try something new. House-Cured Greek sardines with

preserved lemons and pickled peppers challenge the typical fish and chips eaters while meat lovers are given a chance to experience a little snout to tail eating with the Organic Smoked Hangar Steak with

bone marrow, smoked beef tongue ragoût, shiitake mushrooms, foie gras onions, parsnip purée. To finish, there may be a mind bending Verbena Ice cream or bruleed Warm Sweet White Corn Grits with hazelnuts and dried fruit compote.

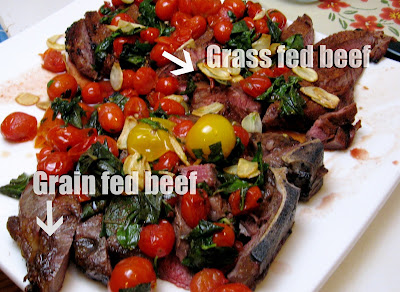

Beyond being delicious, Tony’s food is political. In the dead of winter he refuses to succumb to the urge for ripe tomatoes flown in from Chile and finds inspiration in what is available. Tony’s commitment to stay faithful to local farmers across Massachusetts and neighboring Vermont and New Hampshire not only supports local agriculture in the most difficult months, but also helps to quietly educate his customers about sustainable agriculture and cooking only with fresh and seasonal produce.

Intelligent Cooking

Beside the numerous awards Tony and his restaurant staff have won, one of the most inspiring thing about Tony and his staff at Craigie Street Bistrot is their unyielding commitment to responsible dining and intelligent consumerism. Tony not only cooks great food, but he’s actively engaged in a political and philosophical way of cooking that goes beyond just local eating. Tony creates his seasonally driven dishes from local ingredients that have been raised responsibly and with the greater good of the environment and the eater in mind. Tony may not be the first chef in America to think that local and seasonal cooking is the only responsible

way to run a restaurant (thanks Alice Waters), but he is a powerful spokesperson for responsible consumerism in agriculture.

If you don’t believe me, just read Tony’s thoughtful and intelligent response to a disgruntled customer here. Most chefs are passionate, but few are as thoughtful, political or philosophical about food. With so much about the global economy seeming to be beyond an individual’s control, it’s good to see someone take a stand for a local food economy.

Dream big and make a plan

Now that I’m in my thirties, where I stand in the world makes a whole lot more sense. I know who I am, what I want and what I care about. Despite the years and the thousands of miles, it’s amazing to realize Tony and I actually still share a lot in common. We are political eaters. We love food and are committed to creating great dishes that are not only flavorful but are socially respectful of local agriculture.

By deciding what we eat, or where we eat, we let our dollars do the talking. To quote my new favorite author Michael Pollan, political eating really can make a difference. “At least in this one corner of your life, you will have begun to heal the split between what you think and what you do, to commingle your identities as consumer and producer and citizen.”